Origins

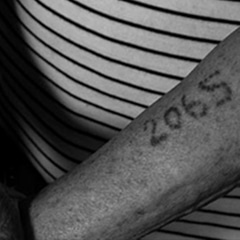

In Auschwitz, the SS camp leaders encountered a problem in late 1940: The rampant death rate of inmates was making it difficult to identify corpses once the clothing showing their registration number had been quickly removed for re-use. The tattoo became a way to assist the murderers in identifying the victims.

Jewish women entering Auschwitz in March 1942 were the first to be tattooed with four-digit numbers. Arrival time and size of the transport determined the serial numbers allocated to the new arrivals. The procedure lasted 30 seconds, and was originally performed with an impractical metal stamp, then a single and finally a double needle device. Lou Sokolov, chief Auschwitz tattooist, and his assistant marked more than 200,000 inmates, almost half the camp population. Soon, more men were required to do the job. In 1944, women were also recruited as tattooists.

Jews arriving in Auschwitz who were selected to be murdered in gas chambers were neither registered nor tattooed. Most inmates selected for slave labour, however, were tattooed. Some inmates were not tattooed: Reich Germans, Ethnic Germans and other non-Jews classified as ‘education prisoners’ or ‘police prisoners’. Unlike Jews and the Roma and Sinti, they were not included in the program of the “Final Solution” and could be discharged from Auschwitz.

The tattoo had three distinct functions: to mark and humiliate prisoners, to prevent their escape and to expedite the identification of corpses already stripped of their uniforms, particularly following mass killings or deaths.

To distinguish between Jewish and non-Jewish tattoos, a small coloured triangle was sometimes added under the tattoo of Jews, indicating that they could be sent to the gas chambers. Some Jews remained untattooed at the request of German industrialists. Upon arrival, they were registered as ‘depot prisoners’ detained temporarily in a transit compound until deported and deployed as slave labourers in war relevant factories throughout Nazi-controlled Europe.

Photographed by Katherine Griffiths

Origins

In Auschwitz, the SS camp leaders encountered a problem in late 1940: The rampant death rate of inmates was making it difficult to identify corpses once the clothing showing their registration number had been quickly removed for re-use. The tattoo became a way to assist the murderers in identifying the victims.

Jewish women entering Auschwitz in March 1942 were the first to be tattooed with four-digit numbers. Arrival time and size of the transport determined the serial numbers allocated to the new arrivals. The procedure lasted 30 seconds, and was originally performed with an impractical metal stamp, then a single and finally a double needle device. Lou Sokolov, chief Auschwitz tattooist, and his assistant marked more than 200,000 inmates, almost half the camp population. Soon, more men were required to do the job. In 1944, women were also recruited as tattooists.

Jews arriving in Auschwitz who were selected to be murdered in gas chambers were neither registered nor tattooed. Most inmates selected for slave labour, however, were tattooed. Some inmates were not tattooed: Reich Germans, Ethnic Germans and other non-Jews classified as ‘education prisoners’ or ‘police prisoners’. Unlike Jews and the Roma and Sinti, they were not included in the program of the “Final Solution” and could be discharged from Auschwitz.

The tattoo had three distinct functions: to mark and humiliate prisoners, to prevent their escape and to expedite the identification of corpses already stripped of their uniforms, particularly following mass killings or deaths.

To distinguish between Jewish and non-Jewish tattoos, a small coloured triangle was sometimes added under the tattoo of Jews, indicating that they could be sent to the gas chambers. Some Jews remained untattooed at the request of German industrialists. Upon arrival, they were registered as ‘depot prisoners’ detained temporarily in a transit compound until deported and deployed as slave labourers in war relevant factories throughout Nazi-controlled Europe.

Photographed by Katherine Griffiths